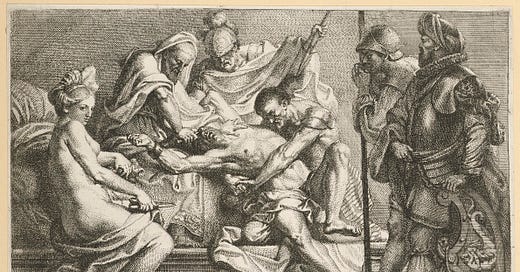

The final poem John Milton wrote explores the last day of Samson’s life. Already in a Philistine prison, slaving away as a drudge for his vengeful overlords, Samson is visited by a few different people before being taken away for a feast in honor of the Philistine fish god, Dagon. He is visited first by a chorus of Israelites, then his father, Manoah, his wife and betrayer, Delilah, and a character not in the Samson story as told in the book of Judges, Harapha of Gath, the giant father of Goliath. Each comes with a different message: the Chorus brings encouragement; Manoah brings comfort and the hopeful promise of a bribed release; Delilah’s arrival is more ambiguous—is she there to make amends or to taunt?; Harapha laments never getting a chance to challenge Samson in battle (and Samson gamely gives him the opportunity right then and there).

Milton titled the poem Samson Agonistes, which does not actually mean “The Agony of Samson” but, more nearly, “Samson the Athlete” or “Samson the Wrestler.” The word “agon” means struggle or contest. It is common, for example, to think of the Middle Ages poem Beowulf as a story of three agons, as Beowulf faces each monster in succession. So, what is Samson wrestling with?

There are a number of things, but the sparring partner I want to focus on here is his sense of destiny. Does God still have a plan for him, despite his buffoonery, infidelity, and captivity?

His beginning lament captures this struggle by recounting the promise:

O wherefore was my birth from Heaven foretold

Twice by an Angel. . .

Why was my breeding order’d and prescrib’d

As of a person separate to God,

Design’d for great exploits. . .

……………………… Promise was that I

Should Israel from Philistian yoke deliver. . . (23-24, 30-32, 39-40)

And yet here he sits, blinded and rotting in a Philistine jail. To Samson’s credit, he does not blame God for his predicament. It is so clearly his own fault—and he spends a lot of the poem lamenting his trust in Delilah—that led to his “impotent” condition. After the arrival of Manoah, Samson even chides his father for blaming God: “Appoint not heavenly disposition, Father,/ Nothing of all these evils hath befall’n me/ But justly; I my self have brought them on,/ Sole author I, sole cause1” (373-376).

And yet, will God’s promise to his people be nullified by the infidelity of the promised vessel? Does Samson’s faithlessness nullify the faithfulness of God? By no means.

Samson is convinced that God is not done with him. This is why he rebuffs Manoah’s efforts to bribe his jailers for his freedom. Samson knows that the true conflict is not between himself and the Philistines but between God and Dagon, the Philistine god whose festival of worship is the occasion of Samson’s revenge at the poem’s end. As God’s appointed instrument, Samson is not done. He can still be used.

This assurance explains Samson’s posture when Harapha the giant comes onto the scene. After seeing off Delilah—whose own purpose in coming, as I’ve mentioned is ambiguous—Harapha rumbles in. As Samson sounds like Milton’s penitent Eve, Harapha sounds like a decidedly unrepentant Satan. He thunders, “thou knowst me now/ If thou at all art known” (1081-1082) which sounds a lot like Satan’s boast to Uriel, “Not to know me argues yourself unknown.” My reputation precedes me, Harapha vaunts.

Samson is having none of it. To Harapha’s long boast, Samson retorts: “The way to know were not to see but taste.” In other words, “come and get some.” Their exchange plays out like this: Harapha taunts Samson at length; Samson responds briskly with some version of “mess around and find out.”

It is clear that Samson intuits a contest with Harapha as God’s further purpose for him. He seizes on Harapha’s confrontation in a way he does not with his father—who offers release—or Delilah—who offers sympathy, sort of, maybe. Harapha’s challenge is much more straightforward and much more within Samson’s wheelhouse. Anyone with remote familiarity with his story in the book of Judges will know that he is anything but reluctant to throw down. Even with Harapha, once he gets a bit more expansive, Samson still refuses to defer blame for his actions. He is resolute in his guiltiness. And yet, being blind does not mean he couldn’t whip a little Philistine giant.

Their encounter ends with Harapha tucking tail and running off, vowing some sort of payback. Why their battle of words does not turn into an actual battle is unclear. Perhaps Harapha is just a coward, in the end, though that seems unlikely. Whatever the reason, Samson is disappointed.

The Chorus tries to encourage him, noting that “patience is more oft the exercise/ Of Saints, the trial of their fortitude” (1288-1289).

His patience is not required for long. After Harapha’s exit, a Philistine official shows up and demands Samson’s presence at a festival. Samson is unsure whether to acquiesce. His labor is one thing; his use at a festival for Dagon is quite another. However, Samson also senses a plan developing. He tells the Chorus, “If there be aught of presage in the mind,/ This day will be remarkable in my life/By some great act, or of my days the last” (1388-1390). He eventually complies with the official, promising the Chorus that he will refuse anything that desecrates the law of God. His death (and the vanquishing of the Philistines) occurs off-stage.

I want to end by saying something that risks sounding cliche. I want to say that this play is designed to teach its reader two things: 1) God’s promises are never void; 2) God’s promises are rarely fulfilled in the manner we envision. Samson (and his parents) envisioned something much different than Israel’s “deliverer” ending his career crushed beneath a pile of Philistine rubble. Nevertheless, the deliverance was effected through this act. In the providence of God, our sin cannot cancel out his good plans.

The first time I read Samson Agonistes was in the spring of 2010. I had just decided to give up the sales game for the grad school game (not as different from each other as I hoped) and was required to take a few “leveling” credits given that I was a Finance major in undergrad and thus bereft of English credits. That semester was amazing; I will always look back on it with great fondness. My Milton professor was that rare bird in the modern academy: an academic who loved what he taught. Dr. Lawson passed on his love for Milton to me and I hope I can thank him someday (in this life or the next). For our semester final, he offered extra credit to students who memorized the final 14 lines of Samson (I still have the passage memorized 13 years later). I’ll print those out below here, both in honor of Dr. Lawson and John Milton and because they accurately and succinctly summarize Milton’s views on the providence of God and the hope we all have to end our lives under the banner of that providence:

All is best, though we oft doubt,

What th’ unsearchable dispose

Of highest wisdom brings about,

And ever best found in the close,

Oft he seems to hide his face,

But unexpectedly returns

And to his faithful champion hath in place

Bore witness gloriously; whence Gaza mourns

And all that band them to resist

His uncontrollable intent,

His servants he with new acquist

Of true experience from this great event

With peace and consolation hath dismist,

And calm of mind all passion spent.

It gives me chills that these were the final poetic words Milton ever wrote. Samson after his striving experienced an oddly peaceful consolation; Milton after a tumultuous and frustrated life seems to have experienced this calm of mind. My prayer is that this would be true for all of us—that even when we doubt or God seems to hide his face, we will trust in his unexpected and glorious return.

Further reading:

My analysis of Eleonore Stump’s chapter on Samson in Wandering in Darkness.

Fellow nerds here will recognize this line as startingly similar to Eve’s confession when confronted about her sinfulness in Paradise Lost. She tells Adam she is the “sole cause to thee of all this thy woe.”