At the beginning of last year, music critic and author Ted Gioia wrote an article that has lived rent-free in my mind since its publication. Called “The State of the Culture, 2024,” Gioia traced a devolution in culture. In his telling, we regressed from an earlier bifurcation between Art and Entertainment where the boundaries between the two could be admittedly blurry to the current state of things. For Gioia, this current state of things is the swallowing up of both Art and Entertainment by Distraction.

I want to be sparing in the use of Gioia’s images, but if you click on the link, you will see an Entertainment fish eating an Art fish and being itself consumed by a bigger Distraction fish. There is, after all, always a bigger fish. So far, so good.

But it gets worse. Distraction itself is being consumed by Addiction. Here’s the visual for that one:

The tech companies that have led us to this depressing impasse don’t care about creating art. They don’t even care about entertainment—most of the junk on Instagram is not even good. Distraction itself is only a means to an addictive end, an infinite scroll of meaningless content.

Gioia classifies this movement as the rise of dopamine culture. His image for this is unforgettable (at least to me):

A lot of us are still operating under the assumptions of the “fast modern culture” in that graphic. I lived through some of those transitions. I remember being mad at a girl I dated in high school because she didn’t listen to whole albums. She barely listened to entire songs. That felt new.

Many evenings in high school and college I sat quietly listening to an entire album from start to finish in order to appreciate the story it was telling. That era was already passing, though, a passing made tangible when a kid on my basketball team gave me a burned CD in 2001 with 18 tracks from 18 different artists. Now, the time it takes to listen to a single song in its entirety seems positively interminable.

The most depressing part of this story is that addiction is not even pleasurable. This is how Gioia describes the phenomenon: “The more addicts rely on these stimuli, the less pleasure they receive. At a certain point, this cycle creates anhedonia—the complete absence of enjoyment in an experience supposedly pursued for pleasure.”

A lot of people reach for their phones and waste an hour gaping at TikTok because they are addicted to the process. It has little to do with entertainment and even less to do with rational thought. Gioia describes the companies responsible for bringing this state of affairs about as the “dopamine cartel.” If you thought Pablo Escobar lived large, wait until you find out how our Silicon Valley overlords live.

All well and good. If you’ve read this far, thank you for not being as easily distracted as the average American.

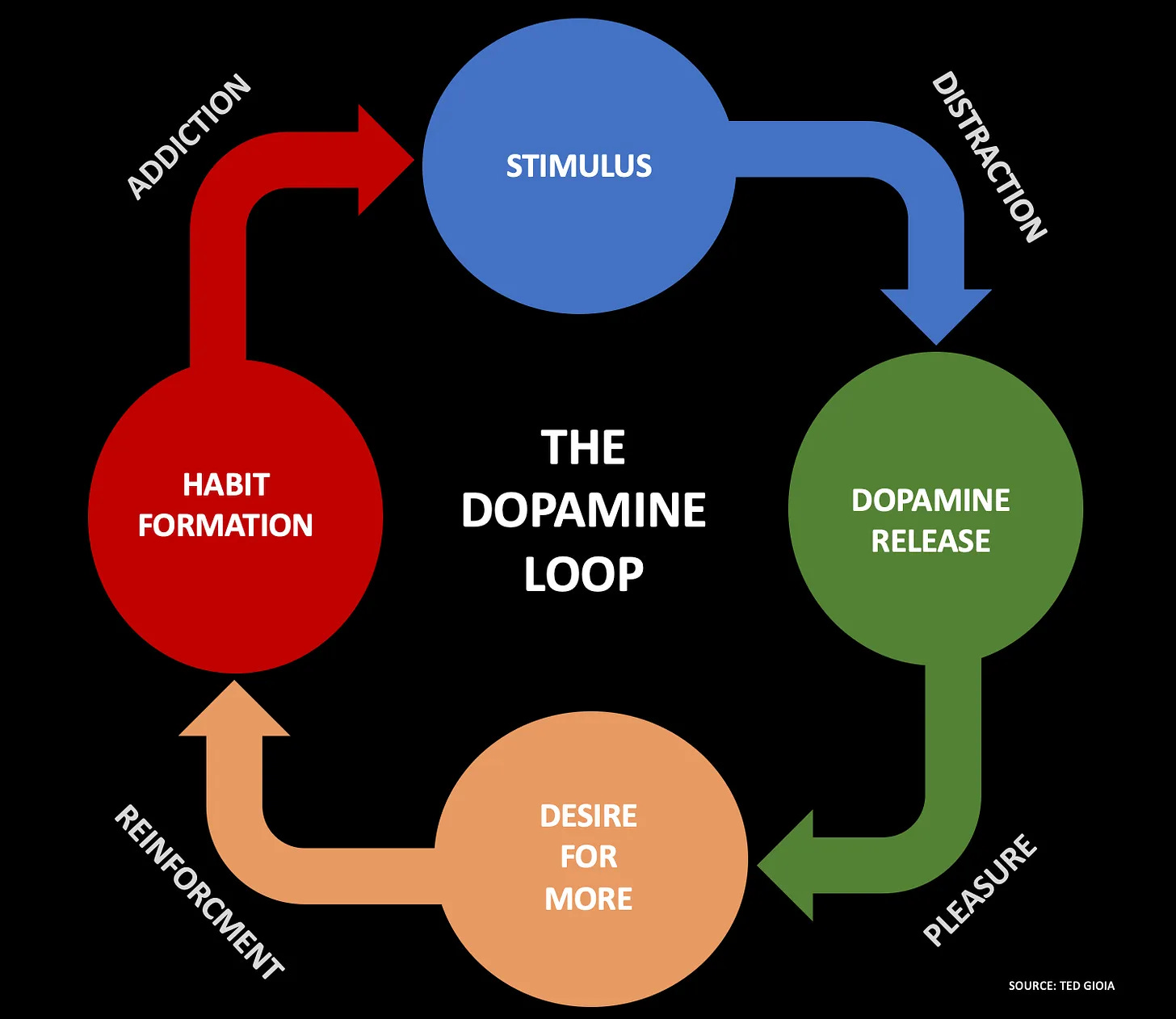

My loftiest goal for 2025 is to opt out, as much as it is possible, from this dopamine world. Here (final image, I promise) is the dopamine loop in visual form:

To remove yourself from this cycle is—in large measure—to remove yourself from American culture. It takes the most intentional of intentionality. And, cards on the table, I don’t possess this now. I read a lot. I write a lot. I work a lot. I spend a lot of time with my kids.

But I am also a dopamine pre-addict. My screen time compares well with the average American (7:04 by one count), but it still robs me of much of the meaning I seek in life.

I want my kids to have zero memories of me staring at a screen. I do not want my children to spell away their childhood, adolescence, and adulthood in that demeaning, head-down, hunched-shoulders posture so common in our age.

My lovely students readily admit that no one looks cool while on their phone. We had to have PSAs when I was a kid about smoking not being cool because smoking actually looks awesome. (Yeah, those PSAs were ineffective.)

We were meant to engage the world with heads up, eyes open, shoulders back, and open to receive what this world has to offer. To adopt this posture requires that we rebuke and reject the most common posture of our age. It is countercultural.

One of the cute—and slightly crude—ways that my students express this to me is around the meme of doing “main character sh*t.” We all want to be main characters. You’ve never watched a great movie where the main character spent the running time staring at his phone.

Let’s cut ourselves out of this loop. Let’s not miss out on what the Lord has called us into because we were lost in a glowing screen.