Happy New Year, everyone! Thanks for signing up for the newsletter. Today’s post commences a series that will take up most of this year. Please read on for more information and consider yourself invited to the project I describe below.

One of my primary reading/writing goals for 2022 is to read John Calvin’s entire Institutes of the Christian Religion and to write about it every day. In reality, as you will see below, this comes down to 250 readings spread across 50 weeks.

An Ambitious Project

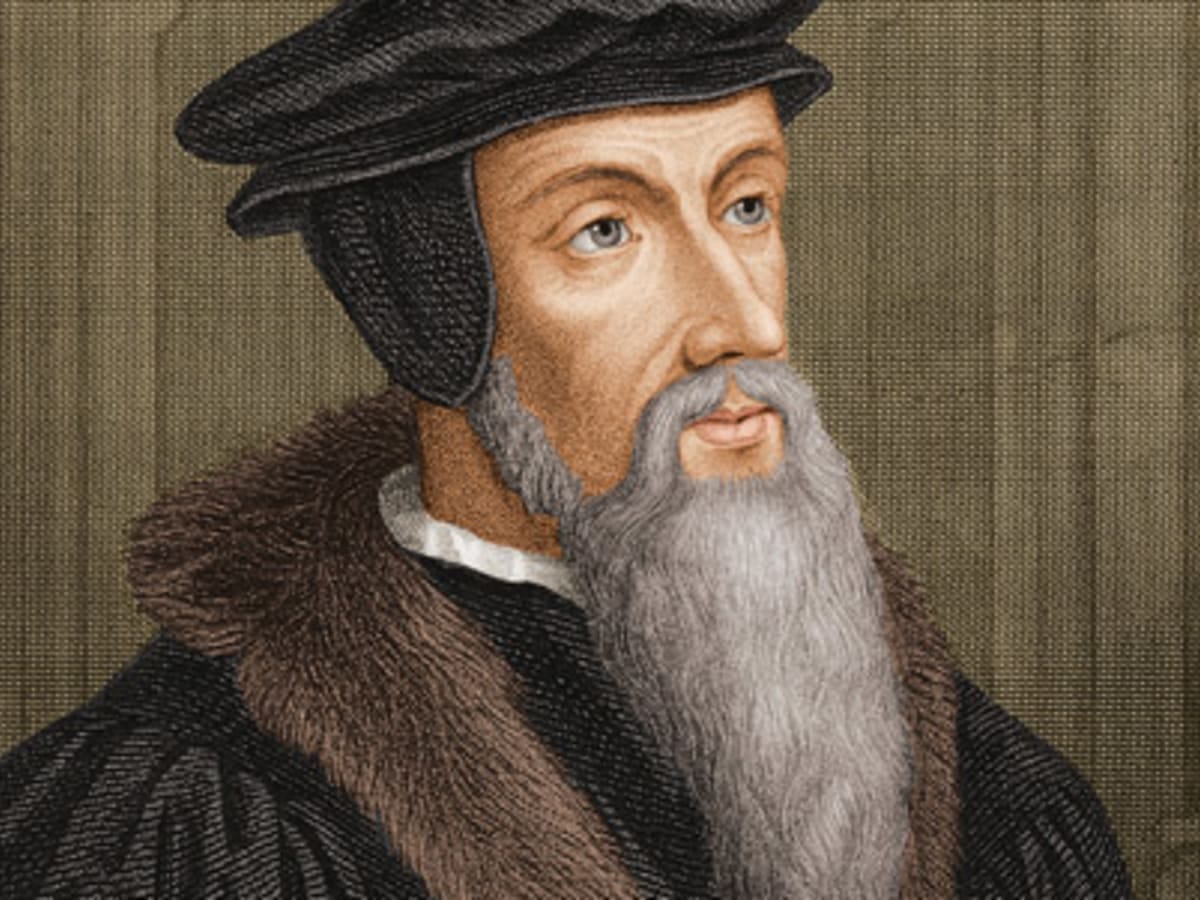

In her essay collection The Death of Adam, which formally introduced me to John Calvin in my early 20s, Marilynne Robinson writes about the French reformer and the movement he spearheaded. In it, she accuses her modern audience of mostly ignoring and casually dismissing the man whose influence has borne so much fruit in the West since his remarkable life. She accuses us in the West of “neglecting him on principle.” “One does not read Calvin,” she goes on to say. “One does not think of reading him.” In a later chapter on Puritanism, she writes that the way we speak of the past is willfully ignorant: “Very simply, it is a great example of our collective eagerness to disparage without knowledge or information about the thing disparaged, when the reward is the pleasure of sharing an attitude one knows is socially approved” (153). Our dismissal of Calvin falls into this broad camp (he is the father of the Puritan movement, after all). We dismiss and disparage not because we know the first thing about him but because to do so is a sort of entry ticket into enlightened society. In the mid-90s, when Robinson wrote, and today even more so, enlightened society is not interested in the depth of our erudition or the amount of time we have spent coming to our conclusions, only that we come to the correct conclusion. Which, of course, happens to be the socially approved conclusion Robinson cites.

And yet the figure of Calvin looms, towers even. To confront him is to stand in the presence of an epochal theological genius. Robinson described Calvin’s theology as follows: “His theology is compelled and enthralled by an overwhelming awareness of the grandeur of God, and this is the source of the distinctive aesthetic coherency of his religious vision, which is neither mysticism nor metaphysics, but mysticism as a method of rigorous inquiry, and metaphysics as an impassioned flight of the soul” (188). Such a figure merits a read, don’t you think?

While I am not necessarily guilty of ignoring Calvin (I teach sections of the Institutes to high school sophomores each year), I do not have the sort of comprehensive knowledge regarding his theology that would allow any opinions that I currently hold to be worthy of any consideration. I have read sections of the Institutes, sections of his various Scriptural commentaries, a couple of biographies, and various articles about Calvin and Calvinism. And yet.

And yet this is a drop in the bucket compared to the reams of literature, criticism, competing theologies, and the vast corpus of his works. I do not hope to exhaust Calvin this year if such a thing were possible. But, I want to end the Year of our Lord 2022 with a better understanding of the man and his mission.

Writing is this strange exponential endeavor. Calvin wrote the first edition of the Institutes in 1536 and substantially revised and expanded the treatise in 1559 (this final edition is what we will be reading). He also translated each edition from the scholarly Latin into vernacular French so that those in his native land could read his systematic theology and defense of the Reformed faith. And here I am--and I stand in the shadows of literally millions of others whose lives have been shaped by the man sometimes labeled the Tyrant of Geneva. And I aim to add another 150,000 or so words to those already poured out upon the man and his work.

The Scope of the Immediate Project

Calvin’s Institutes is a long book. In the edition sitting in front of me now, the work clocks in at a cool 1,800 pages. In it, Calvin attempts to delineate an entire theological view of the world: that of the Reformed church he worked hard to create in Geneva, Switzerland and export around Christian Europe. I plan to write a post on Monday-Friday for 50 weeks this year. I have never even remotely attempted something of this scope before in my writing life. I pray that the Lord gives me strength. In a later section, I will link to the reading plan I will use throughout the year.

Some Supplementary Texts

Alongside the actual Institutes itself, I plan on reading other texts about Calvin, his theology, and its impact on the Western world. A couple of these will be rereads, but most will be new works for me. I am not sure how or when each will pop up throughout the year, but it will undoubtedly imperfectly correspond to the exact places within the Institutes.

A couple of Calvin biographies:

T.H.L. Parker, John Calvin--A Biography

Guides to the Institutes:

David W. Hall, A Theological Guide to Calvin’s Institutes

More General Studies:

Herman J Selderhuis, The Calvin Handbook

Michael Horton, Calvin on the Christian Life: Glorifying and Enjoying God Forever

Matthew Barrett, Reformed Theology: A Systematic Summary

Calvin’s Influence:

John T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism

Curt Daniel, The History and Theology of Calvinism

I don’t know that I will be reading each of these books exhaustively, but I plan to dig deep this year. Time permitting, I am also interested in reading more about the Puritan and Reformed movements as they spread to the UK and the United States (well, what would become the United States). One of Robinson’s arguments in The Death of Adam is that it is difficult to understand American life without understanding Reformation theology. I also studied Calvinism in some depth in preparation for my Master’s thesis on Milton’s political-theological beliefs, and it might be worth dusting off some of those works as well.

An Invitation

I want this to be an interactive endeavor, as much as it can be. Below, you will find links both to the recommended version of the Institutes, translated in the 1950s by Ford Lewis Battles and published in The Library of Christian Classics series, and the reading plan courtesy of the Chapel Library from Mount Zion Bible Church in Pensacola, Florida. I invite you to read along with me, read my thoughts on each section, and add your own. My dearest pedagogical principle is that good, difficult books repay the time we spend reading and attempting to understand them. My earnest hope is that we find this to be true as we explore the work of this contentious character and his most enduring work.